Frequently asked questions

FAQ 1 Question Answer Top FAQ 2 Question Sometimes when I am turning a piece I get a lot of vibration. What is the cause of this and is there anything I can do about it? Answer First check the headstock bearings (and the tailstock revolving centre) to make sure there is no play. They should revolve freely but there should be no sideways movement. Assuming there is no problem with the bearings the following points may be considered. No piece of wood is perfectly homogenous and even when it is turned down to the round a workpiece may be out of balance, ie heavier on one side. If the workpiece is large in relation to the lathe this can cause the lathe to shake. This is most likely to happen with bowls but it can also occur with spindle turning. The most obvious immediate remedy is to run the lathe at a slower speed. If the lathe shakes at the slowest speed available there are two possible tactics. The first is to add weight to the lathe stand using materials such as bricks or sandbags. The second possible solution is to add some counter-balancing weights. A bowl blank, for example could be attached to a large disk - lead weights are then fixed to the disk and adjusted until a reasonable balance is achieved. I have used this method successfully. In the longer term it might be a good idea to beef up the lathe stand and add some extra weight permanently. One way of doing this is to build in a trough which can be filled with bricks or sand. Sand is best because it has a higher damping effect on vibration. Top FAQ 3 Question Is it necessary to cut the corners off a blank before turning between centres? Answer Not usually. Peter Child once said "there is a machine to do this., it is called a lathe" (or words to that effect). The real question is which is the quickest - to set a saw up to do the job or do it on the lathe? There are circumstances in which I think it might be desirable to saw the corners off of a spindle turning blank. One is where the blank is very large in relation to the lathe and might cause vibration. In this case any reduction in weight might be beneficial. (See also FAQ 2 above.) Another is where a batch of items are to be turned. In this case the time taken to set up the saw can be spread over a number of items. Top FAQ 4 Question What wood would you use for a baby's rattle? Answer I have always used ash for my rattles but I must say that I have not actually made a great many. I made them for sale for a while but then decided that, with the kind of litigious climate we have today, it was not worth taking any kind of risk. Having said that I would be quite happy to give one to a grandchild (were I ever to have one). But note should be taken of what I have to say about finishes at the end of my article. Back to wood: I think ash, sycamore, beech, holly or any of the fruit woods should be OK; but the best of these English woods may be beech because it splinters less than any other. I wouldn't wish to take any chances with exotic woods. It seems that all the information regarding toxicity is about the effects of dust. I have never seen any information about the toxicity of wood when it is ingested, so it's an unknown area. Whichever wood is used I would rely on the good sense of the parents to take one of these rattles away from a child if there was any sign that it was chewing the wood away. I have never had any feedback from users at all, so I don't know if it is an issue or not. I have always had great fun making these rattles and I feel that they are very attractive objects in themselves - like little sculptures. So making them can be its own reward. When I used to have them on my stall at craft fairs people used to pick them up and examine them carefully looking for the joins! The last one I made was as a demonstration at our turning club a few months ago. Top FAQ 5 Question I have made your baby`s rattle with which I am quite pleased , but the mini scraper I made from a masonry nail didn`t work very well. I made the handle and glued the masonry nail in and then ground the head but I don`t think I got it right.Is there any chance of a diagram or photo of how it should look when correct. Answer

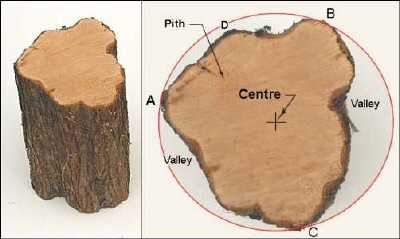

Figure 1 (above) shows three views of a mini-scraper for cutting the left-hand side of a ring. Figure 2 shows a small photograph. The head of the nail is ground as shown. Top FAQ 6 Question I am having trouble visualising how some of the natural edge vases in your gallery are made. Can you help me? Answer   The image on the right (in the above photo) is the view looking straight down on the log. The cross in the middle of the circle is where I place my lathe centre. The points on the wood which touch the circle will be the highest points on the turning, the places where the wood is furthest from the circle will be the lowest points. To find the right place to put my centres I made a polycarbonate (perspex) disk which has a series of circles scribed on it. There is a small hole in the middle. I lay this over the end of the log so that one of the circles touches in as many places as possible and then mark the centre. So, with the centre positioned as shown, the points A, B, and C will be peaks (high points). The places which I have marked ‘valley’ will be low points. The one on the right will be the lowest because the edge of the log at that point is furthest from the circle (or, closest to the centre). Point D will form a minor peak because the wood on either side is farther from the circle. It will be lower than A, B, and C. How deep the minor peaks and the valleys are depends on: (a) the degree of irregularity in the outline of the log; and (b) on the slope of the side of the vase. In practice, when the piece is mounted on the lathe, the imaginary circle is described by the point on the rim which is furthest from the centre point. I always try to get as many points as possible on the circle as I can but I don't always get it right. So I may end up with one point higher than all the others. I always mount the piece between centres to start with. I rough turn the bottom end and then turn a spigot on it to fit my chuck. One way of gaining an appreciation of how the shape comes out, without doing all the hollowing, is to mount an irregular shaped log between centres and turn the outside shape. When doing this you will see the peaks and valleys forming. Top FAQ 7 Question I have just begun turning and am at my wits end on the angles to sharpen my tools. If you can spare a few minutes and give me some starting angles on the basic tools I would be grateful. Answer I am assuming that by the angle to sharpen your tools you mean what I call the 'bevel angle'. How the bevel angle is measured on differrent tools is illustrated in the diagram below. The bevel itself is labelled in diagram. In my opinion the bevel angle is not as important as many people seem to think. I have seen anything from 25 to 45 degrees recommended for chisels. Anything in that range will cut effectively. I sharpen mine at around 40 degrees. Similar considerations apply to bowl gouges. Again for normal use I sharpen mine at around 40 degrees. When I want to keep the bevel rubbing in the bottom of a deep bowl I use a gouge sharpened to 55 degrees. It still cuts but not as well. The bevel angle on spindle gouges can be smaller than on bowl gouges - say 35 degrees. The bevel angle on scrapers is not important. I grind mine at 55 to 60 degrees. What is extremely important on chisels and gouges is the shape of the bevel. It must be either flat or hollow ground. (Note: this does not apply to scrapers.) There is some controversy about how tools should sharpened - in particular about what the grit size should be on the grinding wheel and whether the bevel should be honed. I use a 60 grit wheel and normally I do not hone. Sometimes I use a slip stone in the flute of a gouge to take the burr off the top of the edge. Some pundits pour scorn on this method of sharpening - but it works well enough for me (see my galleries).  |